Focus on Topic - Grand Prix Automobile de Monaco Posters

- 04/05/2022

- William W. Crouse

The first Grand Prix automobile race was held in Le Mans in 1906, and by the 1920s Grand Prix races were being contested in Italy, Spain, Belgium, Great Britain, and Germany.

These races were run in high-priced road cars owned and driven by wealthy men promoting manufacturer’s brands such as Bugatti, Alfa Romeo, Mercedes, FIAT, and Auto Union (Audi). They raced in open cockpits wearing leather helmets, making it a very dangerous sport with frequent crashes and deaths.

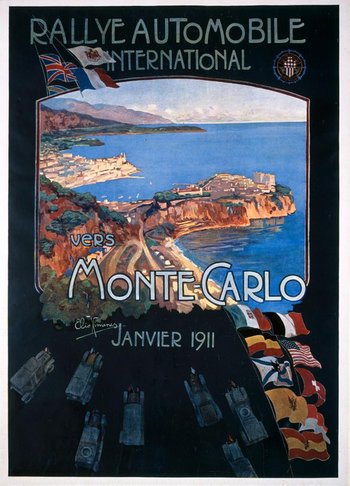

The Automobile Club of Monaco (ACM) sponsored their first auto race in 1911, the Rallye Auto de Monte Carlo. Teams started in six different European cities and raced to Monte Carlo over several days, the team with the fastest time being declared the winner. The ACM wanted to participate in Grand Prix racing, but the International Association wouldn’t grant permission as the Monte Carlo Rallye was run in more than one country. So, in 1928, ACM President Anthony Noghes organized a race to be run in the tiny Principality of Monaco (an area only three miles long and half a mile wide).

In 1929, Monaco became the seventh country to hold a Grand Prix race. It was contested on a two-mile, 100 lap course through the streets of Monte Carlo (now it is a 160 mile, 78 lap race). The Grand Prix de Monaco is considered to be the most glamorous, prestigious, and famous Formula One race. Monaco posters provide a wonderful graphic historical record of the splendor and aura of these races, with the posters from 1930 to the 1960s being incredibly iconic, rare, and beautiful works of art.

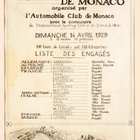

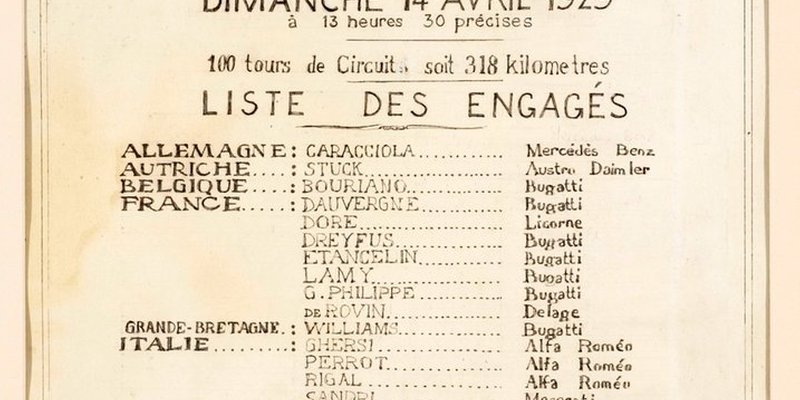

The very first Grand Prix de Monaco poster doesn’t have any real artwork; it just lists the countries involved, the 16 drivers, and the cars entered in the race along with a drawing of the race course. One hundred thousand spectators watched that race won by William Grover in a Bugatti (half the cars in the race were Bugattis). The event took four hours with an average speed of 50 miles/hr. Grover wore a cap—rim to the back—and no protection whatsoever. Prior to taking up racing, he worked as a chauffeur for the Irish painter Sir William Orpen who was famous for having painted the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and Winston Churchill’s favorite portrait of himself. Grover was paid well enough to buy a Bugatti and start racing. He later married Orpen’s former wife and was an agent in the British Secret Service during WWII. He was ultimately captured by the Gestapo and tortured to death.

Monaco posters provide a wonderful graphic historical record of the splendor and aura of these races.

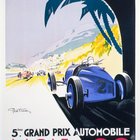

The 1930 Grand Prix de Monaco poster was designed by Robert Falcucci, who was also an historical painter for the French Army. The poster shows Rudi Caracciola driving a muscular white Mercedes Benz SSK directly toward the viewer in a rush of wind and sparks. Monte Carlo recedes into the distance against a blazing sunset. Twelve of the 17 cars in the race were Bugattis, so it was no surprise that a Bugatti driven by Rene Dryfus won. He drove in the first seven Grand Prix de Monaco races. In 1940, he moved to New York City where he would live out the remainder of his life.

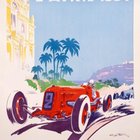

The third Grand Prix de Monaco was held in 1931. The poster for this event was Falcucci’s second, and it is surely one of the greatest Art Deco images in the history of racing poster designs. He shows a red Bugatti racing uphill toward the viewer in the blazing sun with Monte Carlo and the harbor in the distance. A Mercedes SSK #2 is in hot pursuit. The white streaks and concentric arcs perfectly portray their speed, and the red, yellow, and blue colors add plenty of panache. Monegasque Luis Chiron won the race in a Bugatti, the third year in a row for the brand.

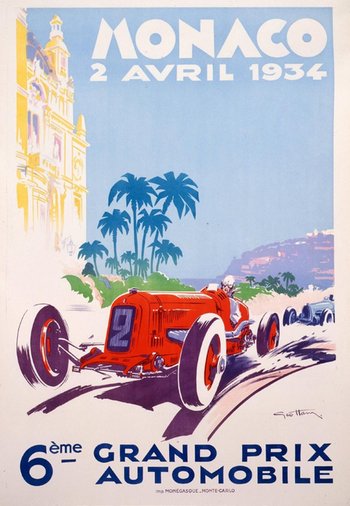

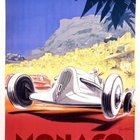

The Falcucci poster for the fourth race in 1934 contrasts the tranquil and sunny slopes of the Riviera with the blur of speeding racers. The Casino and Hotel de Paris are depicted on top of the hill 130 feet above the Mediterranean. Italy’s Tazio Nuvolari won the race in an Alfa Romeo. Considered by many as the greatest driver of all time, he recorded 100 wins, had 17 accidents, and broke almost every bone in his body. In 1932, he won six of the eight Grands Prix contested.

Georges Hamel, known as Géo Ham, designed the next six Grand Prix de Monaco posters (1933-1948). A very talented auto poster artist, he was also a race driver, competing in the 1932 Rallye MC and 1934 24 Heures du Mans.

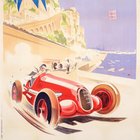

In his Art Deco poster for the 1933 race, we get a view from behind the speeding French blue Bugatti exiting the Tir au Pigeon tunnel, chasing a red Alfa and several other cars as they approach the finish line. Note Ham’s signature use of palm trees and the driver’s scarf blowing in the wind. With the effects of the Depression in full force, only France and Italy—thanks to government subsidies—were able to enter the race. Italy’s Achille Varzi won in a Bugatti, the last Grand Prix de Monaco victory for the brand. The race was a duel between Varzi and Tazio Nuvolari until Nuvolari’s engine gave out on the last lap. Varzi was later killed practicing for the 1948 Swiss Grand Prix.

In the 1934 poster, Ham shows England’s 5th Earl Howe, Francis Curzon, in a red Maserati with a blue Bugatti in the background. Note the palm trees and the scarf again. Algerian Guy Moll won in an Alfa with Enzo Ferrari as their sports director. Moll was tragically killed three months later at age 24 in the Coppa Acerbo. (He was the youngest winner of the Grand Prix de Monaco until Lewis Hamilton won in 2008). Mussolini, recognizing the power and prestige that Grand Prix racing provided for his country, passionately supported the sport. As a result, Italy won all but one race from August 1933 to July 1934-each time in Alfa Romeos.

The 1935 poster was also designed by Géo Ham, as evidenced by the signature palm tree, flying scarf, and the pastel colors. The poster shows a Mercedes Silver Arrow leading a red Alfa with Monte Carlo and Monte Angel in the background. The cars were called “silver arrows” as their white paint was stripped off to make the weight limit. The winner was Luigi Fagioli, who led from start to finish in a Mercedes that averaged 58 mph.

Fagioli also won the Grand Prix de France in 1951 at age 53, the oldest ever winner of a Grand Prix race. As a driver, Fagioli was stubborn and ill-disciplined, and lacked team spirit. Since he was still recovering from severe fractures of his hip and leg, Mercedes named Prussian Manfred von Brauchitsch as their #1 driver in 1934. During the Eifelrennen that year, Fagioli took it on his own to pass Brauchitsch, which infuriated team manager Ferdinand Porsche. He ordered Fagioli to relinquish the lead, so he angrily stopped his Mercedes in the middle of the track and walked back to the pits. Fagioli died in 1952 from injuries sustained while practicing for the Monaco Grand Prix.

Ham’s easily recognizable red scarf is once again blowing in the wind.

Hitler, following Mussolini’s example, understood the benefit to national prestige of winning Grand Prix races. He fervently supported the national team, and as a result, Germany won ten of eleven Grand Prix events in 1935.

In his 1936 poster, Ham depicts a battle between the Germans and Italians, with Auto Union leading a red Alfa through a tight turn. Note the palm tree and the flying scarf once more. The harbor is filled with majestic yachts and the city is in the background. Rudi Caracciola won in a Mercedes. It was raining heavily, and he was a master on wet surfaces (hence his nickname, “Regenmeister”). During World War II, he sought and was given asylum in Italy from Germany despite being a figurehead of the Reich.

In the poster for the ninth race in 1937, Ham reverses the order of the 1936 poster, showing a red Alfa leading the Auto Union and others as they negotiate a corner at Bureau de Tabac along the harbor. The zigzag composition adds to the portrayal of speed. Again, the flying scarf and palm tree. Note Ham’s signature: the “h” looks like a double “t.” The race was won by Manfred von Brauchitsch in a Mercedes. In an act of revenge for the Eifelrennen fiasco in 1935, he ignored signals to cede the lead to Caracciola.

1937 would be the last Grand Prix de Monaco for the next 11 years. The 1938 race was not held due to the economic depression, and 1939 was cancelled as Mussolini forbade Italy to enter France due to the impending start of World War II. Hitler’s Germany won 52 of 55 Grand Prix races from August 1934 to September 1939. It is ironic that he caused the streak to end by starting World War II.

The tenth Grand Prix de Monaco was held in 1948. The poster is signed Géo Matt, inverting the stylish Ham signature. Why? It seems that Georges Hamel (Géo Ham) was imprisoned in 1945 as a fascist. Less plausibly, he may have collaborated with another artist to design the poster. The 1948 poster shows a much more modern blue Arsenal in a demanding uphill climb, with the castle embattlement in the background. Ham’s easily recognizable red scarf is once again blowing in the wind.

The 1948 Grand Prix de Monaco was held after much effort. Each driver took an introductory lap as they were announced and his country’s national anthem was played. Nino Farina won in a Maserati—actually all the 1948 Grands Prix were won by Italian cars, either Alfa or Maserati. No race was held in 1949 due to the death of SAS Prince Louis II on May 9, 1949. His grandson, 26 year old Prince Rainier, succeeded him. Monaco was nearly bankrupt at this point, but a decade later it was back, mainly due to a loan from Aristotle Onassis and the April 19, 1956 wedding of Prince Rainier and the American actress Grace Kelly.

The Grand Prix de Monaco was held in 1950 and 1952, and has been run every year since 1955.