The Polish School of Posters - A Remarkable Period in Graphic Design History

- 08/27/2023

- Harriet Williams- Co founder of Projekt 26 and Projekt Mkt VIntage Poster Market with Sylwia Newman

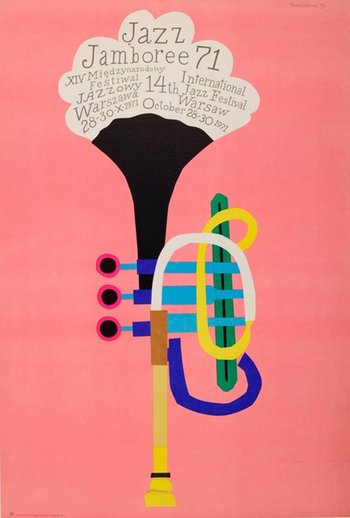

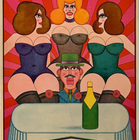

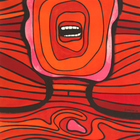

The ‘Polish School of Posters’ is a groundbreaking, yet relatively little known, art movement which emerged from the darkness of post-war Poland. It describes the graphic renaissance which took place during Poland’s Communist years. This was a defining moment in graphic design history, born out of unique circumstances and fuelled by the romantic imaginations and rebellious spirit of the Polish poster artists. The cultural posters designed in Poland during this period reflect the resilient soul of a betrayed nation, and are some of the twentieth century’s most meaningful, original and influential graphic works.

After the Second World War, the ‘Polish People’s Republic’ was placed under strict Soviet rule until 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall. The population, still reeling from the horrors of Nazi occupation, suffered great repression and hardship during this time. As well as the psychological damage which had been wrought; much of the physical landscape had been damaged or destroyed and basic provisions were in short supply. Yet, from here, sprang an explosion of creativity which lasted for decades and spanned three successive generations of artists.

Whilst the Soviet State dismissed fine art as bourgeois decadence, the ephemeral nature of the street poster, and its effectiveness as a relatively cheap means of ‘feel good’ propaganda, enabled this specialist medium to survive as one of the few permitted outlets for professional artists.

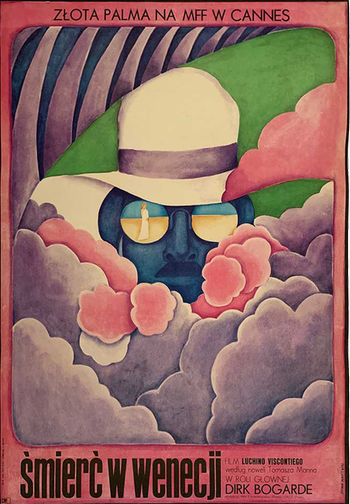

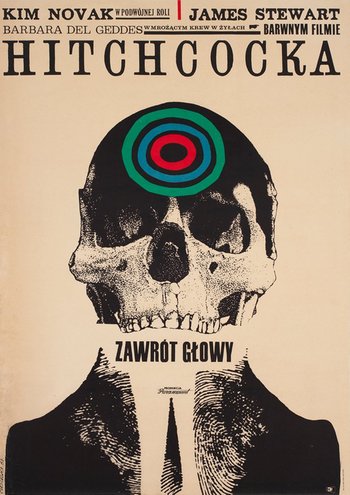

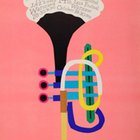

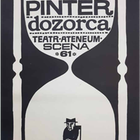

Throughout the fifties, sixties, seventies and eighties the Ministry of Art & Culture commissioned Poland’s most talented artists to design posters for its state-run cultural output; which included films being shown in cinemas, theatre productions, music festivals and events, exhibitions, tourism and the ‘modernised’ state circus.

At first, when a key pioneer of the Polish School of Posters - Henryk Tomaszewski, Professor at Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts - was approached by a representative at the Ministry to design film posters, he was horrified. As a classically trained fine artist he considered the request to be somewhat demeaning. But, with limited options, a few weeks later he agreed to the commission - on the condition that he could forgo the Soviet social realist style and be left to follow his own creative vision. The State agreed; there was simply a stipulation that the posters must reject Western design codes and values. And so, the phenomenon known as the Polish School of Posters was born.

“They didn’t let us do it the way they did it in the West. But also, we didn’t want to.” — Prof. Henryk Tomaszewski

Despite living in a country with strict rules and regulations, the Polish poster artists had gained an unrivalled level of creative freedom from their international peers. Fully financed by the State and unshackled from the constraints of commercial bosses, the Polish School of poster artists flourished. Liberated from adhering to typographic or graphic codes they broke down established design conventions with their highly expressive interpretive approach. The scarcity of materials such as paper, inks and film stills alongside the lack of tools, like official fonts, only fuelled their innovative nature.

Unlike other art movements there isn’t a single aesthetic style which ties the Polish School posters together; instead there is an experimental attitude and a spirit which pervades them all. Polish posters were the first which were designed to be ‘read’; there is a poetic storytelling in Polish posters which goes beneath the surface image. They were also the first to incorporate beautifully hand drawn type and imagery into one cohesive design.

The greatest Polish poster artists each developed a distinctive visual language and identity all of their own. The works of Henryk Tomaszewski, Jan Lenica, Andrzej Krajewski, Jan Mlodozeniec, Waldemar Swierzy, Wojciech Fangor, Franciszek Starowieyski, Roman Cieslewicz, Hubert Hilscher, Mucha Ihnatowicz, Ryszard Kiwerski and Hanna Bodnar, to name but a few, are all utterly unique and instantly recognisable.

“There was no market economy, so there was no need to promote products to consume - but rather to educate and enlighten” — Prof. Andzrej Klimowski

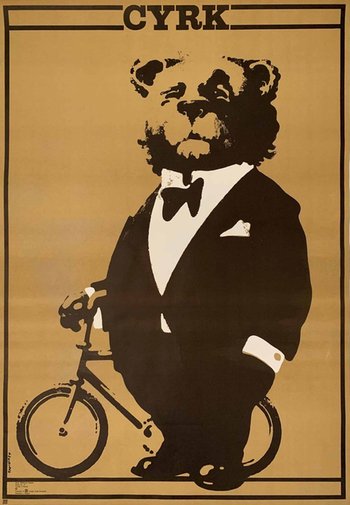

The term the ‘Polish School’ was first coined by Jan Lenica in the 1960s in the title of an article he wrote for Graphis magazine. It referred to the fact that the Polish School of Poster artists never dumbed down to the ‘man on the street’. Instead, they chose to ‘school’ everybody in art appreciation and found many clever ways to introduce subversive thinking into their work. Whilst the artists had to be very careful not to show any political views in their work, they never stopped fighting for the values they believed in. Instead of using violence or force, they took to the streets with their art and infused them with wit and beauty. Despite having to be very subtle in their messaging to get past the censors, the posters are full of hidden symbols and metaphors which convey the artists’ disdain for the regime. Circus posters are great examples of this. On the surface they look playful and fun, but if you look a little closer they can be read as something more. The Tuxedo Bear, for example, represents the overpowering state. The bear was often used as a symbol for the USSR. But here, even though he is all pompous and dressed up, he looks faintly ridiculous with his tiny bicycle.

As bright, bold poster art was pasted on to street kiosks and the fences surrounding bombsites and rebuilding projects, Polish posters not only became beacons of colourful hope on the war-torn streets but began to garner critical acclaim internationally. The Soviet rulers were savvy enough to recognise the benefit in promoting the exceptional work of the Polish poster artists abroad and encouraged the artists.

In 1966 Professor Jozef Mroszczak - another key pioneer of the Polish School of Posters - founded the International Poster Biennale which remains, to this day, the biggest and most prestigious showcase in the world for poster art. Just two years later, in 1968, the first ever poster museum dedicated to this field of art was established in Warsaw. Here the Polish artists were able to display their work and stand shoulder to shoulder with their commercially successful and highly renowned international contemporaries. Despite operating behind the iron curtain, the Polish School of Posters artists had placed themselves firmly on the map as some of the 20th century’s finest graphic artists.

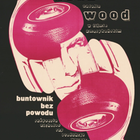

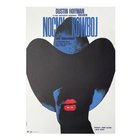

There remains a timeless and contemporary quality to the work of the Polish School of Poster artists. The Polish poster was ahead of its time and endures today as a piece of art. When you compare Polish film posters against the ones produced for the same films in the West, you can see how ground-breaking they were. The iconic Midnight Cowboy, designed in 1973 by Waldemar Swierzy, is a wonderful example of a poster which captures the very essence and dark heart of the film. Highly original, bold and witty Polish posters come with an idea. They are designed to stop you in your tracks, to make you think, to make you feel. Produced after some of Europe’s darkest years, Polish posters are symbols of hope which embody incredible humanity and an inspirational and irrepressible spirit for freedom and survival which is, unfortunately, just as powerful and necessary today.Ryszard Kiwerski - Rebel without a Cause - 1970 Film Poster

In 1966 Professor Jozef Mroszczak - another key pioneer of the Polish School of Posters - founded the International Poster Biennale which remains, to this day, the biggest and most prestigious showcase in the world for poster art. Just two years later, in 1968, the first ever poster museum dedicated to this field of art was established in Warsaw. Here the Polish artists were able to display their work and stand shoulder to shoulder with their commercially successful and highly renowned international contemporaries. Despite operating behind the iron curtain, the Polish School of Posters artists had placed themselves firmly on the map as some of the 20th century’s finest graphic artists.

There remains a timeless and contemporary quality to the work of the Polish School of Poster artists. The Polish poster was ahead of its time and endures today as a piece of art. When you compare Polish film posters against the ones produced for the same films in the West, you can see how ground-breaking they were. The iconic Midnight Cowboy, designed in 1973 by Waldemar Swierzy, is a wonderful example of a poster which captures the very essence and dark heart of the film. Highly original, bold and witty Polish posters come with an idea. They are designed to stop you in your tracks, to make you think, to make you feel. Produced after some of Europe’s darkest years, Polish posters are symbols of hope which embody incredible humanity and an inspirational and irrepressible spirit for freedom and survival which is, unfortunately, just as powerful and necessary today.